For Example: you are allowed to debate how much government we should have, and what kind of government that should be.... but the idea that no government should exist is never given any serious consideration in the mainstream.

Showing posts with label politics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label politics. Show all posts

Saturday, 26 December 2015

"The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum - even encourage the more critical and dissident views. That gives people the sense that there's free thinking going on, while all the time the presuppositions of the system are being reinforced by the limits put on the range of the debate." - Noam Chomsky.

For Example: you are allowed to debate how much government we should have, and what kind of government that should be.... but the idea that no government should exist is never given any serious consideration in the mainstream.

For Example: you are allowed to debate how much government we should have, and what kind of government that should be.... but the idea that no government should exist is never given any serious consideration in the mainstream.

Friday, 6 November 2015

Concrete-Bound

A realisation from Ayn Rand which has really helped me understand the psychology of others is the concept of being "concrete-bound" which took me a while to understand. When I would debate with my dad for example, he would often say things like "well there are very well researched people, as intelligent as you are, who disagree with you" - or (my favourite) "if you ask 100 people the vast majority would disagree" ; not realising these were not actually arguments - never mind valid or sound.

When I would make as obvious reductio ad absurdum like "Well if you asked 100 people if the world was flat in 1066 ..." he would say things like "I don't like your analogies..." as though my example had nothing whatsoever to do with what he said. Ayn Rand helped me realise he was "concrete-bound" he didn't know how to move from a specific example such as "if you ask 100 people they will disagree with you (on this issue)" to the underlying principle of the assertion (the truth is what the majority says it is.) Have you any experiences of interacting with the "concrete-bound" ?

I have found a method of intervening in a way that helps explain the leap but it requires a bit more patience.

You have to first make explicit the principle, "are you saying that if most people believe something then that something is true?" - Wait for them to respond. They are unlikely to say yes, if they say "no - but..." listen to what they have to say and then respond, "But you accept that just because the majority of people say something is true that doesn't mean it is true?" and proceed in the same fashion without hostility so avoid provoking defensiveness.

In other words: don't skip steps in your reasoning, and don't use hidden premises. Take people through the argument stage by stage.

Afterwards you can explain the concept of the particular logical fallacy

When I would make as obvious reductio ad absurdum like "Well if you asked 100 people if the world was flat in 1066 ..." he would say things like "I don't like your analogies..." as though my example had nothing whatsoever to do with what he said. Ayn Rand helped me realise he was "concrete-bound" he didn't know how to move from a specific example such as "if you ask 100 people they will disagree with you (on this issue)" to the underlying principle of the assertion (the truth is what the majority says it is.) Have you any experiences of interacting with the "concrete-bound" ?

I have found a method of intervening in a way that helps explain the leap but it requires a bit more patience.

You have to first make explicit the principle, "are you saying that if most people believe something then that something is true?" - Wait for them to respond. They are unlikely to say yes, if they say "no - but..." listen to what they have to say and then respond, "But you accept that just because the majority of people say something is true that doesn't mean it is true?" and proceed in the same fashion without hostility so avoid provoking defensiveness.

In other words: don't skip steps in your reasoning, and don't use hidden premises. Take people through the argument stage by stage.

Afterwards you can explain the concept of the particular logical fallacy

Friday, 9 October 2015

Tax codes

Apparently Americans spend 6.1 billion a year complying with US tax codes. Wouldn't it be nice if they just replaced the 67,000 pages of tax regulations with the FAIR Tax and everyone could go out volunteering, spending the afternoon with their family, or making something that other people want for some extra cash?

Thursday, 2 April 2015

Capitalism an inherently Statist system?

It has been alleged by persons on the left that capitalism is an inherently statist system. That there has never existed any kind of stateless capitalism or "free market" in any real sense, and that therefore 'to contrast the state with "the market" is just silly.' That under capitalism, statism and the market economy are just two facets of the same hierarchical, totalising system of class rule.

I have heard those propositions put forwards before and I would urge you to reconsider: are the actually - or necessarily - true?

Firstly, I agree that "there are not free markets," but to say there never existed any kind of stateless capitalism or "free market" in any real sense is of no substance really. There had, perhaps, once never been a slave-free statist society, or one where women had the same rights and responsibilities under the law, or one that was not feudal, or a monarchy. So what? Society is a garden where we reap what we sow.

What is silly is not to contrast the state with "the market" but define the free market and the complete opposite of the free market capitalism at the same time! I point, naturally, to corporate welfare, legislations that offer preferential treatment to one service provider over another, subsidisation of domestic producers or protectionist tariffs – all interventions in the market that are not based on the market forces of supply and demand. The state is responsible for almost 50% of the spending in the economy in the UK, and 19% of the population is employed in the public sector. The state controls the money supply, sets the interest rates, and is responsible for regulating each and every facet of the economy from the provision of energy, to the conditions under which someone can employ another person. The state runs the schools, and a great deal of the hospitals. It decides when a road is to be built, and when we are to build a railway. It hands subsidies to tobacco farmers, then taxes the tobacco we smoke. It hands welfare to the wealthy in the form of contracts and preferential legislation, and to the poor in the form of entitlements, free services and food stamps.

The state does not exist because of capitalism, but because the state exists then capitalists are going to exploit it - it would be irrational for them not to do so if it provided more value than serving their customers, just as it would be irrational not to claim housing benefit if you were eligible - but to define the free market (the voluntary exchange of goods and services) and the complete opposite of the free market (state interference in the market) is simply rhetorical sophistry.

It is fallacious to conflate economic power with political power, they are not the same thing. Economic power does not equate to the ability to use force with impunity to achieve your goals. Otherwise Starbucks would lobby McDonalds, and McDonalds would lobby Coca Cola, who were at the same time lobbying Microsoft and Apple. They do not do this. Why? Because the state is the only institution that is able to pass preferential legislations, hand out subsidies and use force and the tax system to enforce them.

If you have a lot of economic power, then even absent the state you can buy a lot things from voluntary sellers: property, factories, machines, natural resources, products, services... but you will soon run low on assets if you are not also creating things that other people want to voluntarily purchase from you. If people are voluntarily purchasing things you produce then you are providing value to them. You are making them better off. Otherwise they would not purchase your goods voluntarily, you would have to coerce them to do so. This is one of the reasons why we voluntarists, anarcho-capitalists, or libertarians (call us what you will) do not want the state. In the market, if you don't like a service you have the power to simply stop buying that service: you don't have to vote for anyone, you don't need to get everyone to agree with you - you just buy something else instead. Not so with government - because you've already bought it. You don't have any choice in the matter. The state it has the power to violate your conscience and force you to pay for it through the tax system, while claiming that you tacitly consent to this violation of your free will to support those causes that you support and divest from those that you do not simply by virtue of living in a particular geographical area.

I have heard those propositions put forwards before and I would urge you to reconsider: are the actually - or necessarily - true?

Firstly, I agree that "there are not free markets," but to say there never existed any kind of stateless capitalism or "free market" in any real sense is of no substance really. There had, perhaps, once never been a slave-free statist society, or one where women had the same rights and responsibilities under the law, or one that was not feudal, or a monarchy. So what? Society is a garden where we reap what we sow.

What is silly is not to contrast the state with "the market" but define the free market and the complete opposite of the free market capitalism at the same time! I point, naturally, to corporate welfare, legislations that offer preferential treatment to one service provider over another, subsidisation of domestic producers or protectionist tariffs – all interventions in the market that are not based on the market forces of supply and demand. The state is responsible for almost 50% of the spending in the economy in the UK, and 19% of the population is employed in the public sector. The state controls the money supply, sets the interest rates, and is responsible for regulating each and every facet of the economy from the provision of energy, to the conditions under which someone can employ another person. The state runs the schools, and a great deal of the hospitals. It decides when a road is to be built, and when we are to build a railway. It hands subsidies to tobacco farmers, then taxes the tobacco we smoke. It hands welfare to the wealthy in the form of contracts and preferential legislation, and to the poor in the form of entitlements, free services and food stamps.

The state does not exist because of capitalism, but because the state exists then capitalists are going to exploit it - it would be irrational for them not to do so if it provided more value than serving their customers, just as it would be irrational not to claim housing benefit if you were eligible - but to define the free market (the voluntary exchange of goods and services) and the complete opposite of the free market (state interference in the market) is simply rhetorical sophistry.

It is fallacious to conflate economic power with political power, they are not the same thing. Economic power does not equate to the ability to use force with impunity to achieve your goals. Otherwise Starbucks would lobby McDonalds, and McDonalds would lobby Coca Cola, who were at the same time lobbying Microsoft and Apple. They do not do this. Why? Because the state is the only institution that is able to pass preferential legislations, hand out subsidies and use force and the tax system to enforce them.

If you have a lot of economic power, then even absent the state you can buy a lot things from voluntary sellers: property, factories, machines, natural resources, products, services... but you will soon run low on assets if you are not also creating things that other people want to voluntarily purchase from you. If people are voluntarily purchasing things you produce then you are providing value to them. You are making them better off. Otherwise they would not purchase your goods voluntarily, you would have to coerce them to do so. This is one of the reasons why we voluntarists, anarcho-capitalists, or libertarians (call us what you will) do not want the state. In the market, if you don't like a service you have the power to simply stop buying that service: you don't have to vote for anyone, you don't need to get everyone to agree with you - you just buy something else instead. Not so with government - because you've already bought it. You don't have any choice in the matter. The state it has the power to violate your conscience and force you to pay for it through the tax system, while claiming that you tacitly consent to this violation of your free will to support those causes that you support and divest from those that you do not simply by virtue of living in a particular geographical area.

Tuesday, 1 October 2013

Exploiting the State

The state is not an effect of capitalism, but because the state exists capitalists will exploit it because the state is the only institution that can pass regulations. Were this not the case, Starbucks would lobby McDonalds, and McDonalds would lobby Coca Cola who were lobbying Microsoft. None of these companies are allowed the use of force, but because of this unique trait - the ability to regulate - it would be the end of any capitalist who had the capacity not to make use of this privilege so long as they had competitors who were willing to do so. These conflicts of interest are foundational to the system in place.

Supposing I am the CEO of a rich corporation and I have $1,000,000 to spend developing my business,

One of my options is to spend that money doing R&D, improving the product, employing highly trained staff, bringing our a better version, or something related which amounts to offering a better service to the consumer. I could also try to advertise it to people I hope will be willing to buy it.

Supposing as a consequence of whatever one of these things I choose to do, then my revenues rise by $1,200,000 then, ok, great! My customers are happier and I have made $200,000

But...

Supposing I can use the $1,000,000 to lobby the state, and they will pass preferential regulations to favour my company, or they will give me other kickbacks or benefits worth - lets say- $1,500,000, then this poisons the whole economy because now I have MORE incentive to engage in bribery and corruption than on pleasing my customers.

I would do this, not because I was evil, but because I was rational. In fact, if I failed to do it I might well be competed out of the market by an actor who did not. Poorer or less established companies cannot do what I just did and so they are a disadvantage against the giants in industry so long as there is a state and the state can be lobbied.

By this process of "unnatural selection" the most successful firms become, not those who are able to best serve their customers, but those who are best able to play the system to get privileges from the government. And it's not necessarily for the evil of all would-be congressmen or parliamentarians either! Even a somewhat integerous politician, who wants to hold office to push through the "least-bad" legislations can only get away with so much before industries begin to back a more complicit candidate to replace them. They really will go to any lengths to retain their special privileges, however unjust, because their livelihoods depend on them.

Perhaps the only solution is making it impossible for politicians to dish out public funds to special interest groups from the public purse, but for this to even be achievable people must be aware of this problem of incentives.

If someone in a business commits a crime they don't get arrested for it because they have this thing called a corporation which takes the blame.

The corporation gets sued, which means the customers pay more and potentially the employees get paid less.

Making the corporation culpable instead of the individuals responsible for making the decisions

removes the moral hazard from the individuals implicated in the unlawful or anti-social behaviour. That's why we see corporation getting away with doing all these horrible things: oil spills, bad bank loans, environmental hazards,

If the individuals personally responsible were at risk of losing their own assets, including their houses - the way an individual who gets sued or fined is - we would ind them far less likely to take these risks.

Sunday, 15 September 2013

What is the difference between Left and Right anarchism?

Left anarchism, which was the common usage of the term up until recently, is a political philosophy very closely related to communism, with the central socialist principle that workers should own the means of production. Having bosses run businesses or capitalists own the means of production is considered to be expploitative and hierarchical, wheras right anarchists see these relationships as acceptible so long as they are voluntary: if employees can agree to contractual terms, quit any time they like, unionise except where probhibited by voluntary agreements, etc. it is considered that the bosses are providing value by organising the work force, and capitalists are providing value by anticipating the market, organising production in terms of demand, and risking their investment (and also their property where uninsured, as the state would not exist to give them limited liability in the form of a Ltd. corporation or Plc.) Right anarchists are not opposed to workers owning their own workplaces as long as this is organised by mutual agreements and voluntary interactions rather than imposed by violations of property rights (eg. workers getting a loan from the bank to buy out bosses and owners.)

Right anarchism is a more recent development but it can also be traced back to Baukunin who is seen as influential to both schools as an anarchist. It's more of an extension of American libertarianism, with the central principle being the NAP - ie. Thou shalt not initiate the use of force - no violence or theft, including taxation, as a rule, although levies for public goods could be extracted through a system of social pressure, ostracism, and refusal to engage in collective buying for people who did not pay their share (eg. If you don't pay your share for street lights you can expect to have to make your own arrangements for garbage collection as well.) Government regulation would similarly be be replaced by a system of insurance companies or cooperatives (often referred to as DROs - dispute resolution organisations) who were financially incentived to solve problems before they occurred instead of being called upon to respond after the fact (like police, government fines, universal sick care, fire fighters, climate taxes etc. and all government services which are called upon only when a problem has all ready arisen.) These companies would lose money through payouts when they failed to protect their clients from harm or loss of property, which would encourage them to develop preventative measures and disincentives to criminals which would be constantly optimised through competition on the free market - whichever organisation was most effective as preventing harm or loss would gain the greatest market share, if someone advanced on their developments they would become lucrative, and if any such company got "too big for its boots," or abused its authority, its clients would have the option to pick another service provider, rather than remain at the behest of a state monopoly for provision of this service.

Left anarchism tends to focus more on problems of capital and capitalism, much like state socialists do. Right anarchists tend to talk primarily about the problems of statism, those which are created or exacerbated by governemnt, and they therefor tend to have the most convincing arguments for the abolition of states.

Despite coming from different angles, both agree that the state is based on force or the threat of force for its existence, that the state is a tool wielded by the ruling class for unfair advantage over everyone else, and that corporations and corporatism are products of statism which allow the rich to privilege from privatizing gains and socialising losses, which is immoral.

All forms of anarchists acknowledge that where there are rulers there can be no rules, as rulers by their very nature, make themselves the exception to the rule. Anarchists are egalitarians, no special privileges for law-makers or corporations. If you kill, harm, steal, or damage someone else's property, you are to be held personally liable for it - not the state (tax payer) or corporation (consumer/share-holder) - you personally. There is to be no hiding behind institutions which are mere abstractions of the mind in anarchy. This implementation of this moral hazard for the privileged is meant to do away with much of the corruption, cronyism, and war crimes which are part and parcel of statist societies.

So some common ground between the two despite philosophical difference on very key points.

For example, left wing ideals such as workers running their workplaces are thought by some to be more likely under right anarchism that statism, since the public education system trains children for individualism and competition, but the evidence on how individuals learn best is in favour of a cooperative learning environment. Without the kind of schooling which is prevalent and imposed by the state (which right anarchists are strongly opposed to) children would be raised with lots of experience of cooperation and mutualism, and so would more likely to create workplaces that capitalised on those skills than top-down hierarchies which follow the prevalent pattern of schooling and parenting.

Right anarchism is a more recent development but it can also be traced back to Baukunin who is seen as influential to both schools as an anarchist. It's more of an extension of American libertarianism, with the central principle being the NAP - ie. Thou shalt not initiate the use of force - no violence or theft, including taxation, as a rule, although levies for public goods could be extracted through a system of social pressure, ostracism, and refusal to engage in collective buying for people who did not pay their share (eg. If you don't pay your share for street lights you can expect to have to make your own arrangements for garbage collection as well.) Government regulation would similarly be be replaced by a system of insurance companies or cooperatives (often referred to as DROs - dispute resolution organisations) who were financially incentived to solve problems before they occurred instead of being called upon to respond after the fact (like police, government fines, universal sick care, fire fighters, climate taxes etc. and all government services which are called upon only when a problem has all ready arisen.) These companies would lose money through payouts when they failed to protect their clients from harm or loss of property, which would encourage them to develop preventative measures and disincentives to criminals which would be constantly optimised through competition on the free market - whichever organisation was most effective as preventing harm or loss would gain the greatest market share, if someone advanced on their developments they would become lucrative, and if any such company got "too big for its boots," or abused its authority, its clients would have the option to pick another service provider, rather than remain at the behest of a state monopoly for provision of this service.

Left anarchism tends to focus more on problems of capital and capitalism, much like state socialists do. Right anarchists tend to talk primarily about the problems of statism, those which are created or exacerbated by governemnt, and they therefor tend to have the most convincing arguments for the abolition of states.

Despite coming from different angles, both agree that the state is based on force or the threat of force for its existence, that the state is a tool wielded by the ruling class for unfair advantage over everyone else, and that corporations and corporatism are products of statism which allow the rich to privilege from privatizing gains and socialising losses, which is immoral.

All forms of anarchists acknowledge that where there are rulers there can be no rules, as rulers by their very nature, make themselves the exception to the rule. Anarchists are egalitarians, no special privileges for law-makers or corporations. If you kill, harm, steal, or damage someone else's property, you are to be held personally liable for it - not the state (tax payer) or corporation (consumer/share-holder) - you personally. There is to be no hiding behind institutions which are mere abstractions of the mind in anarchy. This implementation of this moral hazard for the privileged is meant to do away with much of the corruption, cronyism, and war crimes which are part and parcel of statist societies.

So some common ground between the two despite philosophical difference on very key points.

For example, left wing ideals such as workers running their workplaces are thought by some to be more likely under right anarchism that statism, since the public education system trains children for individualism and competition, but the evidence on how individuals learn best is in favour of a cooperative learning environment. Without the kind of schooling which is prevalent and imposed by the state (which right anarchists are strongly opposed to) children would be raised with lots of experience of cooperation and mutualism, and so would more likely to create workplaces that capitalised on those skills than top-down hierarchies which follow the prevalent pattern of schooling and parenting.

Monday, 19 August 2013

Kids Today

Saying that "kids today are out of control" is kind of like referring to the victim of domestic abuse as "jittery." Well, perhaps they are jittery, but we have no way of knowing until they are in a neutral, nurturing environment where we can see what they are really like.

Saturday, 9 February 2013

Why doesn't beef cost 7 times as much as grains?

If it takes 7 times as much grain to create the same amount of beef, so why isn't beef 7 times as expensive as grain? Because the vast majority of farming subsidies go to meat and dairy farmers. In other words we are forced to pay for the mistreatment of animals whether we can conscience it or not. Fruits an vegetables have increased in price faster that other products and they are the building blocks of health, while confectionaries have gone down in price in real terms and they destroy the quality of life. If we could end these subsidies the whole society would be healthier, we would also save NHS money on preventable illnesses that could be allocated to those who still needed it. What is more, Western agricultural subsidies for domestic farmers have been a horrendous catastophe for the poor in the developing world, because excess produce is dumped there putting their own producers out of a livelihood and building their own economy. Crazy world we live in, where money is shifted from the people to self-interest groups at the point of a gun, despite the harm it does to the whole of society.

Monday, 31 December 2012

The "Free Rider" Problem is NOT a Problem for Anarchy.

Here is one of what might be a series of articles on the practicality of the abolition of states because I'm tired of getting into the same conversations with statists who think they are original but actually just have identical objections to every other statist.

The "Free Rider" Problem is NOT a Problem for Anarchy.

When you say you disagree with states as a concept people very often say something like "How will you get streetlights?????" Of course, you can substitute for street lights any other thing that the government happens to have a monopoly on doing at the moment, and you really have to wonder, if government provided ball bearings and had a monopoly on that would statitsts be saying, "How would we get steering wheels without government? That's maaaaaadness."

This is called the free-rider problem, and it's one of the most basic problems in economics. If you have a public good that many people benefit from, how do you stop people who don't pay from benefitting?

What I find most frustrating is people raise these objections as though all of the anarchists suddenly have to go have to go "Bah dub a duh duh good point I have never thought of that before, you're right, boo for anarchism, that's insurmountable, I'm now a statist... yup, giving all the guns to a single central authority who are allowed to violently extract income for everyone and distribute it as they might to whoever bribes them, or whomever they want to bribe to vote for them, sounds like a muuuuuch better solution. How very rational."

Such a basic objections, when they are presented with accompanying smugness rather than genuine curiosity, are kind of insulting to your intellegence, because you'd have to be an idiot not to have thought of these problems. You get to wishing people would just pick up a book and learn a little about a theory before assuming they can knock it down in one blow.

Their argument basically goes ... "I get such-and-such for free and don't have to raise a finger, therefore the system in place is adequate."

But that does not logically follow. Just because there is a system in place does not meant is good, efficient, cheap, practical, suitable long term, preferable to what could be in it's place, etc.

What is in effect being argued, is that the combined ingenuity of every individual in society who may have a versted interest in solving the free-rider problem when it comes to street lighting say, or quite frankly anything, is going to be inferior to the cenral dictat of a bunch of beaurocrats who are not even spending their own resources, and have less vested interest in solving any given problem than of bribing people to vote for them.

The make a "state of the gaps" argument and will forever point to this hole or that hole which is something which the state has monopolised and therefore cannot be met by another institution, be it a business, charity, consumer or worker cooperative, community project, or any other institution which is voluntary. They want you to say how exactly an endless list of things will be provided without a state, if you can't answer even one of them they go "Ha! See! Anarchism, doomed to fail."

The unreasonably biased nature of this line of questioning, which does not subject an ideology which has been responsible for killing 2-300 million of it's own people in the last hundred years not including the wars, to the same scrutiny and need for evidence of the ideology they oppose, is only eclipsed by it's irrationality.

Firstly, if the free rider problem is a serious problem, then the government is the worst culprit, because they can grant themselves and their buddies special priveleges with public money which isn't theirs like no other institution in society, and everyone else would have to pay for it. Not only can they, they do.

And more, asking me, or any other anarchist, how exactly this or that would be done in a stateless society is no different from asking an abolitionist how cotton will be picked once slavery is abolished. It would have been literally impossible for anyone to accurately predict that the abolition of slavery would make human labour uneconomic and lead to the invention of great big heaving robots that run on dinosaur juice from thousands of years ago, but that's what happens. When you remove the arbitrary dictats of how things should be done by force, something better rushes in to fill the place, it's compelled to by trial and error. Statism is not trial and error, it's "lets do it this way and ban anyone from doing it any other way." That is why when you look at statist institution they seem frozen in time, but there is a new smartphone with better features every couple of years. How will street lights be provided? In whatever way optimises through trial and error - banning people from trying alternatives by making the government option mandatory certainly can't help in any way. How could it?

We must note that the free rider problem is only a problem in cases where people consider it to be a problem. For example, if I mow my lawn my neighbour may benefit from his house having a higher value due to the aesthetics of the community, but I am very unlikely to demand remuneration for it. So we can conclue that our discussion of solutions is limited to cases where people receive external benefits from other peoples time or resources in ways which bother payers.

In such cases, maybe people who paid would get stickers on their doors and people who could pay but didn't would get dirty looks and prying questions from their neighbours who wouldn't have any business with them. Or maybe the lighting organisation would offer special priveleges to people who did pay like cheaper electricity for their house. Or maybe people who didn't pay would have to pay more for insurance because they weren't paying in to the safety of their community. Who can tell?

The "Free Rider" Problem is NOT a Problem for Anarchy.

When you say you disagree with states as a concept people very often say something like "How will you get streetlights?????" Of course, you can substitute for street lights any other thing that the government happens to have a monopoly on doing at the moment, and you really have to wonder, if government provided ball bearings and had a monopoly on that would statitsts be saying, "How would we get steering wheels without government? That's maaaaaadness."

This is called the free-rider problem, and it's one of the most basic problems in economics. If you have a public good that many people benefit from, how do you stop people who don't pay from benefitting?

What I find most frustrating is people raise these objections as though all of the anarchists suddenly have to go have to go "Bah dub a duh duh good point I have never thought of that before, you're right, boo for anarchism, that's insurmountable, I'm now a statist... yup, giving all the guns to a single central authority who are allowed to violently extract income for everyone and distribute it as they might to whoever bribes them, or whomever they want to bribe to vote for them, sounds like a muuuuuch better solution. How very rational."

Such a basic objections, when they are presented with accompanying smugness rather than genuine curiosity, are kind of insulting to your intellegence, because you'd have to be an idiot not to have thought of these problems. You get to wishing people would just pick up a book and learn a little about a theory before assuming they can knock it down in one blow.

Their argument basically goes ... "I get such-and-such for free and don't have to raise a finger, therefore the system in place is adequate."

But that does not logically follow. Just because there is a system in place does not meant is good, efficient, cheap, practical, suitable long term, preferable to what could be in it's place, etc.

What is in effect being argued, is that the combined ingenuity of every individual in society who may have a versted interest in solving the free-rider problem when it comes to street lighting say, or quite frankly anything, is going to be inferior to the cenral dictat of a bunch of beaurocrats who are not even spending their own resources, and have less vested interest in solving any given problem than of bribing people to vote for them.

The make a "state of the gaps" argument and will forever point to this hole or that hole which is something which the state has monopolised and therefore cannot be met by another institution, be it a business, charity, consumer or worker cooperative, community project, or any other institution which is voluntary. They want you to say how exactly an endless list of things will be provided without a state, if you can't answer even one of them they go "Ha! See! Anarchism, doomed to fail."

The unreasonably biased nature of this line of questioning, which does not subject an ideology which has been responsible for killing 2-300 million of it's own people in the last hundred years not including the wars, to the same scrutiny and need for evidence of the ideology they oppose, is only eclipsed by it's irrationality.

Firstly, if the free rider problem is a serious problem, then the government is the worst culprit, because they can grant themselves and their buddies special priveleges with public money which isn't theirs like no other institution in society, and everyone else would have to pay for it. Not only can they, they do.

And more, asking me, or any other anarchist, how exactly this or that would be done in a stateless society is no different from asking an abolitionist how cotton will be picked once slavery is abolished. It would have been literally impossible for anyone to accurately predict that the abolition of slavery would make human labour uneconomic and lead to the invention of great big heaving robots that run on dinosaur juice from thousands of years ago, but that's what happens. When you remove the arbitrary dictats of how things should be done by force, something better rushes in to fill the place, it's compelled to by trial and error. Statism is not trial and error, it's "lets do it this way and ban anyone from doing it any other way." That is why when you look at statist institution they seem frozen in time, but there is a new smartphone with better features every couple of years. How will street lights be provided? In whatever way optimises through trial and error - banning people from trying alternatives by making the government option mandatory certainly can't help in any way. How could it?

We must note that the free rider problem is only a problem in cases where people consider it to be a problem. For example, if I mow my lawn my neighbour may benefit from his house having a higher value due to the aesthetics of the community, but I am very unlikely to demand remuneration for it. So we can conclue that our discussion of solutions is limited to cases where people receive external benefits from other peoples time or resources in ways which bother payers.

In such cases, maybe people who paid would get stickers on their doors and people who could pay but didn't would get dirty looks and prying questions from their neighbours who wouldn't have any business with them. Or maybe the lighting organisation would offer special priveleges to people who did pay like cheaper electricity for their house. Or maybe people who didn't pay would have to pay more for insurance because they weren't paying in to the safety of their community. Who can tell?

Personally

I'd rather not be forced on threat of being put in a cage with

murderers and rapists to pay for these things, I'd take my chances with

someone being able to see all the solutions offered to me by people who have a real incentive to organise the best

system and present the options to the people in my street, or the

company that built the roads, or the one who built the houses, or whoever is responsible for making these decisions, so we can

choose for ourselves.

Friday, 9 November 2012

Contract law is an abomination. (prototype)

This is a prototype article and I am collecting feedback to improve it and address counter arguments.

Everyone knows that contract laws are litigious and that's why people have to train for so long to be lawyers, but what is the benefit of contract law being handled by the centralised monopoly of the state, when having third parties compete to insure contracts would optimise the process by having lots of great minds working on producing better, simpler and more easier to use models. Likely the best amongst these highly trained lawyers and judges would find fantastic work providing the full service of their skills for those end.

If you and I were wanting to go into business we could seek the arbitration of a third party who could insure our contracts. The more we did business well, the cheaper this would be as we were "trust worthy" and our premiums would go down and down, much like a no-claims bonus for not causing a road accident. If one of us reneged upon our contract, our third party would have to compensate the party that lost out on the deal and would likely never insure the person who broke the deal again until they had compensated them. They could also contact all the other companies that were providing the service and warn of the unworthiness of this client so their premiums for doing business in future would go through the roof.

What though, is someone was willing to renege on a "one time deal" for say $2.5 million and then they could just live happily upon their ill-gotten gains for the rest of their lives? Well, who would insure a contract for $2.5m without the appropriate assurances that their client would pay? Jail time for reneging could easily be written into the contract and voluntarily agreed upon by the parties engaging in the process. But that is just one option. Given the number of people who would be working in the field, surely their combined ingenuity would come up with better solutions than any either of us could come up with as mere individuals playing the game of philosophy.

The idea that the state is required to enforce contracts is not only misgiven, it's a complete waste of tax money for private individuals to subsidise agreements between corporations and other people they have no associations with to pay the inflated salaries of lawyers and judges who could have more important things to do within the criminal justice system such as handle violent criminals. In the meantime lawyers can charge upwards of £100 for writing a letter, or for the privelege of an hour of their time, because the service they provide has become incomprehensibe to the clients they are providing it to and impenetrable to anyone who has not jumped through the government hoops. Surely if alternatives were available society would soon do better.

Everyone knows that contract laws are litigious and that's why people have to train for so long to be lawyers, but what is the benefit of contract law being handled by the centralised monopoly of the state, when having third parties compete to insure contracts would optimise the process by having lots of great minds working on producing better, simpler and more easier to use models. Likely the best amongst these highly trained lawyers and judges would find fantastic work providing the full service of their skills for those end.

If you and I were wanting to go into business we could seek the arbitration of a third party who could insure our contracts. The more we did business well, the cheaper this would be as we were "trust worthy" and our premiums would go down and down, much like a no-claims bonus for not causing a road accident. If one of us reneged upon our contract, our third party would have to compensate the party that lost out on the deal and would likely never insure the person who broke the deal again until they had compensated them. They could also contact all the other companies that were providing the service and warn of the unworthiness of this client so their premiums for doing business in future would go through the roof.

What though, is someone was willing to renege on a "one time deal" for say $2.5 million and then they could just live happily upon their ill-gotten gains for the rest of their lives? Well, who would insure a contract for $2.5m without the appropriate assurances that their client would pay? Jail time for reneging could easily be written into the contract and voluntarily agreed upon by the parties engaging in the process. But that is just one option. Given the number of people who would be working in the field, surely their combined ingenuity would come up with better solutions than any either of us could come up with as mere individuals playing the game of philosophy.

The idea that the state is required to enforce contracts is not only misgiven, it's a complete waste of tax money for private individuals to subsidise agreements between corporations and other people they have no associations with to pay the inflated salaries of lawyers and judges who could have more important things to do within the criminal justice system such as handle violent criminals. In the meantime lawyers can charge upwards of £100 for writing a letter, or for the privelege of an hour of their time, because the service they provide has become incomprehensibe to the clients they are providing it to and impenetrable to anyone who has not jumped through the government hoops. Surely if alternatives were available society would soon do better.

Saturday, 3 November 2012

Psychohistory

I believe childrearing is the birth of society.

According to the data, countries who use less phsical punishment have less violent crimes, democracy emerged first in countries where parenting styles moved over to less authoritarian and more democratic, countries with dictatorial parenting styles tend to be dictatorships. The shaping of childrearing is the shaping of the whole society. For more data, The Origins of War in Child Abuse by Lloyd deMause, and anything by psychoanalyst Alice Miller are excellent authoritative works in the field.

According to the data, countries who use less phsical punishment have less violent crimes, democracy emerged first in countries where parenting styles moved over to less authoritarian and more democratic, countries with dictatorial parenting styles tend to be dictatorships. The shaping of childrearing is the shaping of the whole society. For more data, The Origins of War in Child Abuse by Lloyd deMause, and anything by psychoanalyst Alice Miller are excellent authoritative works in the field.

Wednesday, 24 October 2012

eBay don't pay all their taxes? Good!

Here's an

interesting but controversial thought experiment.

In response to this article in the Guardian claiming that eBay has avoided some £50m in taxes, a friend of mine was asking around to see if there was any alternative she could use because she wanted to boycott them.

I asked her to expand on her reasons why, because I thought that the government would only spend the money on wars, corporate welfare, paying off the bankers and their cronies anyway, so what was the point?... She kindly responded:

"It would mean less of an excuse for austerity measures; if they're seen to be collecting the funds, and still cutting the welfare state. The government is very good at shifting the blame - but if places like Starbucks, IKEA, and eBay actually paid taxes, then the government has nowhere to hide."

My thought was that while those propositions may hold true in a socialist utopia, they are actually based on a basic misapprehension of economics which is quite common, particularly on the left, which is that it is actually possible for corporations to pay taxes. In truth, as the (very liberal) Senator, Mike Gravel, put in his book Citizen Power a Mandate for Change (2008) under the chapter which advocates for tax reform (in line the Fair Tax proposals):

"Liberals bristle at the thought of relieving corporations of income taxes. Unfortunately... fooled into thinking that by taxing corporations they shift the cost of government from the people to corporations. Corporations do not pay taxes; they merely collect taxes from their consumers for the government, In fact, a corporate tax is a disguised retail sales tax....

In response to this article in the Guardian claiming that eBay has avoided some £50m in taxes, a friend of mine was asking around to see if there was any alternative she could use because she wanted to boycott them.

I asked her to expand on her reasons why, because I thought that the government would only spend the money on wars, corporate welfare, paying off the bankers and their cronies anyway, so what was the point?... She kindly responded:

"It would mean less of an excuse for austerity measures; if they're seen to be collecting the funds, and still cutting the welfare state. The government is very good at shifting the blame - but if places like Starbucks, IKEA, and eBay actually paid taxes, then the government has nowhere to hide."

My thought was that while those propositions may hold true in a socialist utopia, they are actually based on a basic misapprehension of economics which is quite common, particularly on the left, which is that it is actually possible for corporations to pay taxes. In truth, as the (very liberal) Senator, Mike Gravel, put in his book Citizen Power a Mandate for Change (2008) under the chapter which advocates for tax reform (in line the Fair Tax proposals):

"Liberals bristle at the thought of relieving corporations of income taxes. Unfortunately... fooled into thinking that by taxing corporations they shift the cost of government from the people to corporations. Corporations do not pay taxes; they merely collect taxes from their consumers for the government, In fact, a corporate tax is a disguised retail sales tax....

...they

simply take the tax into account as an added cost of production… and adjust

their prices accordingly... close examination of the tangled corporate tax

structure shows it only serves to inflate the cost of goods and services to

consumers... Obviously, if we eliminated all corporate taxes and subsidies, the

ordinary tax payer would come out far ahead."

These words are not from a reactionary Republican or Thatcherite, but from one of the most liberal senators in the American political system, who became nationally known for his forceful but unsuccessful attempts to end the draft during the Vietnam War and for putting the Pentagon Papers into the public record in 1971 at risk to himself, and then throughout his career campaigned for direct democracy, an end to war, transparency in government, universal healthcare, social security, and all the other trappings of a left-of-centre Democrat.

These words are not from a reactionary Republican or Thatcherite, but from one of the most liberal senators in the American political system, who became nationally known for his forceful but unsuccessful attempts to end the draft during the Vietnam War and for putting the Pentagon Papers into the public record in 1971 at risk to himself, and then throughout his career campaigned for direct democracy, an end to war, transparency in government, universal healthcare, social security, and all the other trappings of a left-of-centre Democrat.

That might be pretty hard to apprehend because it arouses our sense of

injustice that the big boys can get around paying while small business owners

and the rest of us tax cattle have to put in for stuff we don’t agree with

(like the wars) but perhaps once we realise that this tax money is not being

extracted from the bank accounts of rich CEOs, but us independent eBay users the

case may becomes clear. We foot the bill.

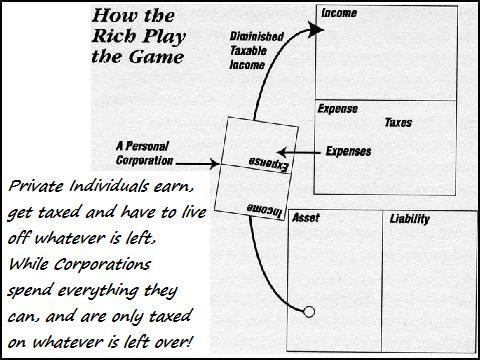

Rich

people don’t pay income tax the same way we do. They have these handy things

called corporations. Private individuals earn, get taxed and live off what is

left. Corporations earn, spend, and are taxed on what it’s left, check out this

handy diagram from Rich Dad, Poor Dad

(2000) Robert T. Kiyosaki:

Remember, the status of “Corporation” is a privilege granted to certain

companies by the state rather than the

free market. If you

wanted to tax the receipts of "greedy capitalists" the option would

be to place tax on share dividends, although perhaps even those could craftily

be passed on to the consumer.

The truth

is, if eBay were forced to pay their taxes, all that would likely happen is

that they’d raise the price of listing products. The cost will be passed on to

the consumer and be borne by buyers and sellers. It's certainly very unlikely

to do any good in the world.

eBay is one of the biggest employers in the world, allowing around 350,000 people to work from home and have more leisure time. It facilitates recycling and ends wastage by putting people who want second hand products in touch with people who have those products and no longer need them. It even has a feedback system which allows people to indicate who is trust worthy to exchange with and who is not. There are punitive consequences for not honouring your word, much unlike in the political realm where those who don't keep campaign promises escape unscathed, and those guilty of far greater crimes and misdemeanours under the guise of foreign policy (or even domestic policy) seem to walk above the law.

eBay is one of the biggest employers in the world, allowing around 350,000 people to work from home and have more leisure time. It facilitates recycling and ends wastage by putting people who want second hand products in touch with people who have those products and no longer need them. It even has a feedback system which allows people to indicate who is trust worthy to exchange with and who is not. There are punitive consequences for not honouring your word, much unlike in the political realm where those who don't keep campaign promises escape unscathed, and those guilty of far greater crimes and misdemeanours under the guise of foreign policy (or even domestic policy) seem to walk above the law.

eBay enriches

the lives of millions of people, allowing them to afford things they couldn't

otherwise or make a bit of money on the side instead of chucking things out.

To

clarify the point, if we are talking about McDonald's who, we’ve been told, cut

down the rainforest, or Coca Cola who are said to monopolise, discriminate and

poison, or British Gas who are part of a state-granted cartel of the energy

industry which continues to increase prices while enjoying higher profits, to

the detriment of elderly customers who may freeze to death this winter... If

such a company is dodging taxes, by all means go ahead, boycott them. I'd

boycott them anyway on a moral principle, perhaps it will make them less

competitive.

But eBay? eBay isn't only harmless, it's is a credit to society.

But eBay? eBay isn't only harmless, it's is a credit to society.

The state, on the other hand, is a non-voluntary institution which institutes corporate monopolies by regulating into place barriers to entry. It makes war, kills more people than all private individuals and corporations put together, provides corporate welfare to the rich, makes nuclear weapons, sells arms to foreign dictators and subsidises nuclear and unsustainable energy despite the risks. It forces people at gun point to pay for indoctrination camps where their children are forced to do what they are told when they are told, habituating them to living in a hierarchical society before they ever enter the work place, and then after 11-13 years of this state-led ‘education’ most come out with so few skills that are economically valuable that they cannot even find minimum wage job. It puts people in cages with violent criminals and rapists if they happen to have the wrong kind of vegetation in their pocket, and at great expense to the tax payer, despite all the reason and evidence showing that drug prohibition has never worked, does not work, will never work - that addiction should be treated as a public health issue rather than a criminal one - and that those countries who have moved in the direction of legalisation or even decriminalisation have had the most positive outcomes. The state spent the younger generation into 1 trillion pounds of debt before they were even born by the act of buying votes from the older generation by giving them public services that they were not paying for themselves with their own tax money, and by printing money which inflated and devalued the currency to the benefit of the elite and detriment of the poor. And then on top of all that, as though that were not enough, they had the cheek to sell the tax payer further down the river by bailing out the bankers who were largely responsible for the economic crisis to the tune of £500 billion pounds in 2008.

The

government has the power to force you to pay for all these immoral things

whether you agree with them or not. Whether you like them or not. You are bound

to by law.

On the other hand, eBay can't force you to pay for a single thing your conscience disagrees with. Literally nothing. Ever.

On the other hand, eBay can't force you to pay for a single thing your conscience disagrees with. Literally nothing. Ever.

And I’m

supposed to believe that eBay dodging their taxes is the larger social issue at

stake here?

Supposing one of us were put in charge of a real life award of fifty million pounds.

Supposing one of us were put in charge of a real life award of fifty million pounds.

We were

told that the other judges had narrowed down the decision to two anonymous candidates,

and that they needed us to pick one of the two choices as a tie breaker.

All we

were given to base our decision on was a brief summary of what each of these bodies

had done, say, since eBay's inception in 1995. Those would include, on one side,

the wars and expenses scandals for example, and on the other side a charge of

infringing on patents (2000) and accusations of fleecing clients with an increase

in charges (2008) to name a couple. Could either of us honestly say, given all

the information in an essentially unbiased way - a way uncontaminated by the

social-bias which says paying taxes is virtuous by its very nature, while

avoiding them is necessarily vicious - that we would give the award to the more

violent party?

I'm pretty sure I know who I'd give the money to, if I happened to have the choice, and it wouldn't be the institution that had all the guns.

I'm pretty sure I know who I'd give the money to, if I happened to have the choice, and it wouldn't be the institution that had all the guns.

Tuesday, 16 October 2012

I was spanked and I deserved it!

Supposing you were spanked for violent antisocial behaviour, lets say, biting another child.

Some say in this instance they "deserved" physical punishment.

But just because you acted out in violence, does not mean there was not alternative ways of educating you not to repeat the behaviour or not to act violently. How can violence teach a child not to use violence to get what they want? It can only teach them that it's ok for the more powerful party to use violence.

There are also environmental factors that would have shaped you into the kind of child who would bite.

What would spanking do to reverse those? The likelyhood is none whereas there are other methods of educating children which could have.

It could be that you were very angry, and had you been taught how to express anger effectively and non-violently you never would have bit in the first place. It could be if you were taught those skills in response to your behaviour, that you would never feel the inclination to bite another child again, nor do other things that were violent or in other ways felt unpleasant to other individuals the next time you were angry. It could be that you'd still be able to use whatever skills you learned then as a child you would still find served you today. You'd be well practiced in them by now and use those skills to your benefit and to benefit those around you.

When a child is spanked they are fundamentally short changed of a proper developmental education in two ways:

1) They are taught to be selfish - as they are taught by the implication that they should perform some "naughty" action because of the negative consequences to themselves, as opposed to based on an empathetic understanding of how such an action negatively affects another.

2) They miss out on the opportunity to learn from other non-violent methods that can teach them how to reason, be sensitive to others, be sensitive to themselves and manage their own behaviour. To develop genuine values that concern caring about the consequences of their actions, and learn talents that can serve them in adult life where the use of violence and force is unacceptible.

There are other ways of dealing with children biting other children that build lasting values that remove the need to scare children into a front of acting social.

Some say in this instance they "deserved" physical punishment.

But just because you acted out in violence, does not mean there was not alternative ways of educating you not to repeat the behaviour or not to act violently. How can violence teach a child not to use violence to get what they want? It can only teach them that it's ok for the more powerful party to use violence.

There are also environmental factors that would have shaped you into the kind of child who would bite.

What would spanking do to reverse those? The likelyhood is none whereas there are other methods of educating children which could have.

It could be that you were very angry, and had you been taught how to express anger effectively and non-violently you never would have bit in the first place. It could be if you were taught those skills in response to your behaviour, that you would never feel the inclination to bite another child again, nor do other things that were violent or in other ways felt unpleasant to other individuals the next time you were angry. It could be that you'd still be able to use whatever skills you learned then as a child you would still find served you today. You'd be well practiced in them by now and use those skills to your benefit and to benefit those around you.

When a child is spanked they are fundamentally short changed of a proper developmental education in two ways:

1) They are taught to be selfish - as they are taught by the implication that they should perform some "naughty" action because of the negative consequences to themselves, as opposed to based on an empathetic understanding of how such an action negatively affects another.

2) They miss out on the opportunity to learn from other non-violent methods that can teach them how to reason, be sensitive to others, be sensitive to themselves and manage their own behaviour. To develop genuine values that concern caring about the consequences of their actions, and learn talents that can serve them in adult life where the use of violence and force is unacceptible.

There are other ways of dealing with children biting other children that build lasting values that remove the need to scare children into a front of acting social.

Sunday, 23 September 2012

Debunking the Nuclear Renaissance

ok I rustled this up for you tell me what you think

The nuclear industry was economically dead for decades. In 2005 the American Congress breathed 12 billion tax payer dollars to bring it back from the brink, and where there is nuclear power the same state-capitalist croneyism follows the world over. Without free money from the public sector, the nuclear industry does not survive. No one would insure a nuclear powerplant on a free market because it simply wouldn't be worth the risk. Instead states take liabily.

Nuclear power was never really introduced to produce energy as such, it was used in the 50s as a front for producing plutonium for nuclear weapons and to offset the cost somewhat. Time and time again it's proven itself be the most expensive form of energy production.

The anti-greenhouse argument for nuclear energy is very weak. Fossil fuel energy is needed to mine uranium and transport it, produce the cement and transporting that too, build the reactor, deal with the waste and many other processes. Then there is the processes of purifying what comes out the ground (which is becoming increasingly inpure.) This itself create a lot of carbon emissions and puts poison chemicals into the ground. The radioactity that was released from uranium mining in into the environment many decades ago still poisons the landscape, the water, and damages health - when the Uranium-235 is split it gives off polutants that affect the air, water, ditches... Mining for the fuel has been an environmental disaster which has destroyed the lands of native peoples like American Indians and Aboriginies. As supplies become rarer and rarer more sites need to be located for aquiring it at the expense of natural landscapes and indigenous peoples.

Conservation of Energy bests producing more every time. In one study students found that every pound spent on energy efficiency saved seven times as much carbon as every pound spent on nuclear power. In 1993 the book Energy Without End by Michael Flood featured a house built in British Columbia, which has a climate similar to South England, that received an Annual Electric Heating Bill of £12. It was four times the size of an average British house.

Heat is thrown away from our powerstations, poured into the sky as flue gases and steam. Instead this "waste steam" could be piped in order to heat homes an workplaces, afterall, what is the best way to eliminate hypothermia which kills many elderly people in their own homes evey winter? To produce more energy at great cost and hope they can afford it or to insulate their houses so that they retain heat at less expense? The government should spend money on grants for insulation instead of nuclear power. Energy efficiency also creates more jobs.

We have a lot better chance of making solar and wind work now than we have of isolating the enormous amounts of nuclear waste that are being created every day. Plutonium 239, just one of the bi-products, has a half-life of 24,400 years - 4 times longer than recorded history! It could takes over 500,000 years for even a small quantity of it to become harmless. The lethal dosage is a thousandth of a gram.

Wasting money on the irresponsivle act of producing pqwer through nuclear fission inhibits us as a society from making the leap to sustainables. Perhaps future generations will never forgive us for leaving them our nuclear legacy to manage but perhaps we can stop adding fuel to the nuclear fire.

The nuclear industry was economically dead for decades. In 2005 the American Congress breathed 12 billion tax payer dollars to bring it back from the brink, and where there is nuclear power the same state-capitalist croneyism follows the world over. Without free money from the public sector, the nuclear industry does not survive. No one would insure a nuclear powerplant on a free market because it simply wouldn't be worth the risk. Instead states take liabily.

Nuclear power was never really introduced to produce energy as such, it was used in the 50s as a front for producing plutonium for nuclear weapons and to offset the cost somewhat. Time and time again it's proven itself be the most expensive form of energy production.

The anti-greenhouse argument for nuclear energy is very weak. Fossil fuel energy is needed to mine uranium and transport it, produce the cement and transporting that too, build the reactor, deal with the waste and many other processes. Then there is the processes of purifying what comes out the ground (which is becoming increasingly inpure.) This itself create a lot of carbon emissions and puts poison chemicals into the ground. The radioactity that was released from uranium mining in into the environment many decades ago still poisons the landscape, the water, and damages health - when the Uranium-235 is split it gives off polutants that affect the air, water, ditches... Mining for the fuel has been an environmental disaster which has destroyed the lands of native peoples like American Indians and Aboriginies. As supplies become rarer and rarer more sites need to be located for aquiring it at the expense of natural landscapes and indigenous peoples.

Conservation of Energy bests producing more every time. In one study students found that every pound spent on energy efficiency saved seven times as much carbon as every pound spent on nuclear power. In 1993 the book Energy Without End by Michael Flood featured a house built in British Columbia, which has a climate similar to South England, that received an Annual Electric Heating Bill of £12. It was four times the size of an average British house.

Heat is thrown away from our powerstations, poured into the sky as flue gases and steam. Instead this "waste steam" could be piped in order to heat homes an workplaces, afterall, what is the best way to eliminate hypothermia which kills many elderly people in their own homes evey winter? To produce more energy at great cost and hope they can afford it or to insulate their houses so that they retain heat at less expense? The government should spend money on grants for insulation instead of nuclear power. Energy efficiency also creates more jobs.

We have a lot better chance of making solar and wind work now than we have of isolating the enormous amounts of nuclear waste that are being created every day. Plutonium 239, just one of the bi-products, has a half-life of 24,400 years - 4 times longer than recorded history! It could takes over 500,000 years for even a small quantity of it to become harmless. The lethal dosage is a thousandth of a gram.

Wasting money on the irresponsivle act of producing pqwer through nuclear fission inhibits us as a society from making the leap to sustainables. Perhaps future generations will never forgive us for leaving them our nuclear legacy to manage but perhaps we can stop adding fuel to the nuclear fire.

Monday, 27 August 2012

"I was spanked and I turned out fine."

"Not was I beaten, but I was given a smack if I was too naughty. There's a difference."

"Actually according to brain scans there IS no difference in the effects on the brain between spanking and more serious forms of physical abuse, because the punishment still has to be at least scary enough to get you to change your behaviour.

Most of us were spanked. That doesn't mean it's right.

Not long ago most people would smoke in the same room as their children, but we know better now.

The only people who spank are people who don't know better methods exist, or are reluctant to accept the evidence because it means accepting that their parents were wrong to hit them, which is not an easy thing to do for anyone.

50 years ago it was acceptable to hit your wife for being "disobedient"

but we know better now

Hitting doesn't teach people not to be naughty out of any values at all.

Hitting just teaches people "do what I say because you'll get hurt if you don't."

It's got nothing to do with doing the right things because, say, other people will get hurt when you don't - That's a value.

If I leave my wallet on the counter at a party, I don't want no one to steal it because they'll go to prison, I want no one to steal it because they have empathy and understand I would hate to have my wallet stolen. I'd have to cancel my cards, get a new student ID, etc. etc. That is called a value. Not stealing because you're afraid of punishment is NOT a value.

So when you spank you're doing two bad things:

1) you're teaching kids to be selfish - ie. don't do this because of the consequences to you (as opposed to the consequences to others)~

2) you're missing the opportunity to use other methods which will teach your children both how to reason and think for themselves, and genuine values that concern caring about the consequences of their actions.

Here are the facts on spanking, according to the last 20-30 years of science (NOT my opinion.)

children who are physically punished even mildly:

- Tend to have a lower IQ and are less able to reason effectively.

- Have a poorer relationship with their parents than those who are reared non-aggressively.

- Are more likely to resort to violence as a means of solving problems and even become chronically defiant.

- Are more likely to smoke and twice as likely develop alcohol/drug addictions.

- Are more likely to develop anxiety disorders and depression and show symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

- Are more likely to display anti-social behaviour and abuse their spouse or children later in life.

The use of aggression on the young gains immediate compliance but results in more aggressive children prone to delinquency, anti-social behaviour and crime. The consequences correlate to dose, the more physical punishment, the greater the effects, and effects tend to reduce once physical punishment stops.

While many of parents justify spanking, 85% say they would rather not if there was an alternative.

93% of studies on spanking agree It is harmful to children. This has been called "an almost unheard of consensus" in childrearing studies - in other words people who reasearch childrearing find it hard to agree on just about anything, but that spanking is harmful is just about as close to an established fact as you can get.

Hitting is very short sighted, it gets what you want in the moment but creates problems in the long term.

Like if part of your roof was rotting and you just patched it over, it might stop water coming in for now, but you'll suffer in the long run as it will be much harder to fix

A list of studies can be found here: http://

"Actually according to brain scans there IS no difference in the effects on the brain between spanking and more serious forms of physical abuse, because the punishment still has to be at least scary enough to get you to change your behaviour.

Most of us were spanked. That doesn't mean it's right.

Not long ago most people would smoke in the same room as their children, but we know better now.

The only people who spank are people who don't know better methods exist, or are reluctant to accept the evidence because it means accepting that their parents were wrong to hit them, which is not an easy thing to do for anyone.

50 years ago it was acceptable to hit your wife for being "disobedient"

but we know better now

Hitting doesn't teach people not to be naughty out of any values at all.

Hitting just teaches people "do what I say because you'll get hurt if you don't."

It's got nothing to do with doing the right things because, say, other people will get hurt when you don't - That's a value.

If I leave my wallet on the counter at a party, I don't want no one to steal it because they'll go to prison, I want no one to steal it because they have empathy and understand I would hate to have my wallet stolen. I'd have to cancel my cards, get a new student ID, etc. etc. That is called a value. Not stealing because you're afraid of punishment is NOT a value.

So when you spank you're doing two bad things:

1) you're teaching kids to be selfish - ie. don't do this because of the consequences to you (as opposed to the consequences to others)~

2) you're missing the opportunity to use other methods which will teach your children both how to reason and think for themselves, and genuine values that concern caring about the consequences of their actions.

Here are the facts on spanking, according to the last 20-30 years of science (NOT my opinion.)

children who are physically punished even mildly:

- Tend to have a lower IQ and are less able to reason effectively.

- Have a poorer relationship with their parents than those who are reared non-aggressively.

- Are more likely to resort to violence as a means of solving problems and even become chronically defiant.

- Are more likely to smoke and twice as likely develop alcohol/drug addictions.

- Are more likely to develop anxiety disorders and depression and show symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

- Are more likely to display anti-social behaviour and abuse their spouse or children later in life.

The use of aggression on the young gains immediate compliance but results in more aggressive children prone to delinquency, anti-social behaviour and crime. The consequences correlate to dose, the more physical punishment, the greater the effects, and effects tend to reduce once physical punishment stops.

While many of parents justify spanking, 85% say they would rather not if there was an alternative.

93% of studies on spanking agree It is harmful to children. This has been called "an almost unheard of consensus" in childrearing studies - in other words people who reasearch childrearing find it hard to agree on just about anything, but that spanking is harmful is just about as close to an established fact as you can get.

Hitting is very short sighted, it gets what you want in the moment but creates problems in the long term.

Like if part of your roof was rotting and you just patched it over, it might stop water coming in for now, but you'll suffer in the long run as it will be much harder to fix

A list of studies can be found here: http://

Monday, 13 August 2012

Teaching Kids to be Loving

When I was a volunteer in school, I never once shouted at, threatened or punished a child, nor bribed a child to do what I wanted them to with "positive reinforcement" like the promise of a gold star or a treat ---- Most, if not all of the other teachers were strict disciplinarians, but time after time I got specifically put with the most difficult children in the class, because it didn't take long for them to see that I was excellent at dealing with them: they didn't go out of control, or when they did, I found ways to help them regain it quickly enough.

Yes, there were challenges, but if I had just hit those kids I would have never learned to overcome those challenges in all the amazingly ingenious ways I was forced to. I never would have learned what motivated those children when they were being difficult, or what was real for them in those moment when they were being challenging.